It is a great art to die well and to be learnt by men in health…Place your coffin in your own eye: dig your own grave. -Jeremy Taylor, 1665

Death. It is an unavoidable aspect of all human life, but in our culture it is a taboo subject – discussed only when necessary, and even then, usually in a whisper. Centuries ago, however, the reality of death was embraced – not surprising – considering that the average life span was around 45 years. Beautiful objects and jewelry were created to remind people of mortality. These objects of adornment, most often rings, are referred to as Memento Mori – a succinct term reminding us of our transience on Earth, and a warning to prepare ourselves for whatever other realm awaits us. Such jewelry graphically illustrates the transitory nature of life – we will all meet the same end. The Latin translation of the term Memento Mori is, simply, “remember you must die.”

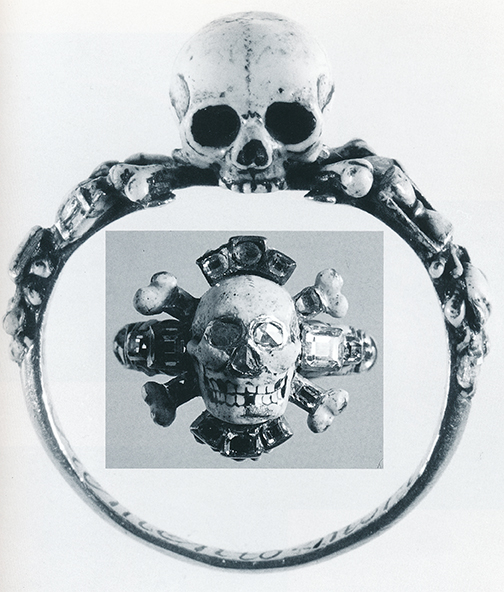

Only jewelry can convey a harsh reality in such an elegant form. Its popularity lasted for over 300 years, and was in customary wear in some form until the early 20th century. While Memento Mori jewelry dates back to ancient times, most of the earliest examples we see are from the 15th century, with inscribed messages on the pieces that conveyed the warning of imminent death. Symbols soon became en vogue and replaced text, particularly the image of a death’s head: the remainders of life—bones and skulls—symbolize what once existed. Full length skeletons offered a different design option in the creation of Memento Mori jewelry. Many other symbols were also prominent: worms, snakes, graves and bats were all prevalent within the scope of Memento Mori iconography. Memento Mori jewelry has many variations in design, from the outright blatant expressions of death to the more subtle and beautiful implications of mortality through intricate details.

A great example of early Memento Mori jewelry is a charm from the 16th century of an enameled skeleton in a coffin from the Victoria and Albert Museum. Its literal symbolism conveys the importance of life and its beauty through the exquisitely detailed scrolling design of the coffin’s top. The inscription reads: THRONGH. (sic) THE. RESVRRECTION. OF CHRISTE. WE. BE. ALL. SANCTIFIED. Such a statement can only imply that the wearer believed that there is no need to fear death: through faith, peace can be found at the end of life. How can one not be intrigued by the skeleton in his coffin, resting with his hands crossed, prepared for the unknown?

The skull motif is the prominent icon of Memento Mori jewelry. Although there are many examples, it’s especially interesting to find a piece that is definitive in its statement of mortality. I’m quite partial to this watch from 1660 from the British Museum: a skull whose head opens to reveal a clock face. The style was a popular one, a representation of the societal celebration of both life and death. This example is both breathtaking and charming in its details. With engravings along the skull, the piece becomes much more contemplative. There are four inscriptions:

“vita fugitur” – life is fleeting (engraved across the front temple)

“caduca despice” – look down upon a fallen thing (on the right side)

“aesterna respice” – look upon eternity (top left side)

“incerta hora” – the hour of death is uncertain (at the back of piece, engraved alongside an hour glass)

The Latin phrases, the skull, and the depiction of time all translate to the constant reminder of the owner’s mortality. Time is precious, and should not be wasted. A watch (tempus fugit) combined with these symbols was the perfect constant reminder.

Deceptively simple, this 18th century Memento Mori ring from the Victoria and Albert Museum is overflowing with meaning. I love this example because the understated style of the ring is heightened by the symbolism of the enamel and the rock crystal setting. On the black enameled gold, the word MEMENTO MORI is inscribed. Additionally, intricate iconographic symbols such as a skull and crossbones, a pickaxe and shovel, and gravedigger’s tools are portrayed. The most interesting feature of the ring is the oval faceted crystal encasing a piece of black silk. The fabric is quite textural, as if a snake had shed its skin and the remains of the creature had been preserved and set underneath the clear rock in order to outlast decay. Made in 1719, this exquisite piece of jewelry is powerful despite its delicacy and grace.

The skull rings, often with the skull set on crossed bones, was a popular and very graphic design. The skulls were usually realistically enameled, and often opened to reveal a message. One English ring of this description, circa the mid 1660’s, opens to reveal the nude torso of a woman enveloped in flames, which might have been a reminder of the great London Fire of 1666 or of the Plague. Another quite similar skull ring opens to reveal the carefully enameled sentiment, in French, that Death is the end of remembrance. One interesting ring I have seen is a gold band with an incised skull and bones filled with black enamel – it dates from the beheading of King Charles 1 of England in 1649, and bears the engraved inscription inside the band “Prepare to followe” (sic).

Close to the body and invaluable to the soul, Memento Mori jewelry offered a constant reminder of time and the fleeting gift of life. Decay of the tangible (the body) and the remainders of what once existed (the skeleton and skull) encompass the meaning of Memento Mori. Ultimately, Memento Mori jewelry remains as a lesson: remember you must die—the hour will not be known. Thus, every day must be lived as if it’s your last and cannot be taken for granted. Life and death are both beautiful and must be embraced.

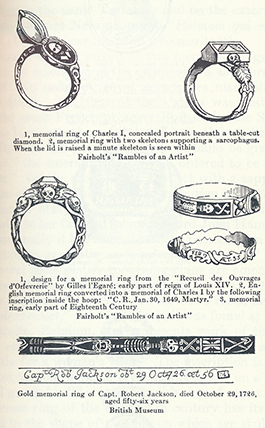

Memento Mori jewelry can be easily confused with its first cousin – Memorial jewelry, which has a long history as well. Much of the same iconography was used for both, especially for the earlier Georgian memorial pieces. Dating from the 16th – 19th centuries, skulls, skeletons, coffins and even cherubs adorned rings, which were the favored pieces of jewelry for this purpose. Pearls represented tears.

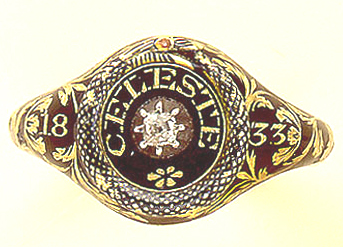

Memorial jewelry, however, differed from Memento Mori in that the pieces were made to commemorate the death of an important and/or beloved person. The band was usually in black enamel on gold, but is also found in white, usually for a woman. Often, the band had scrolled segments, with the name, date of birth, date of death and age of the deceased. More rarely, the band was solid, with an elongated skeleton in either black or white. Often, the ring centers a faceted optical crystal in the form of a coffin, with a tiny enameled skeleton inside. Sometimes, just a skull, and I have seen one with a skull accompanied by a cherub on each side. Occasionally, these could be rather humorous, such as one Stuart crystal ribbon slide I have seen with a skeleton lying jauntily on its side atop a coffin. Jewelers of the day must have kept a little supply of tiny skulls and bones, so that the client could design the piece to suit. The individual elements are sewn on with a single human hair – often, onto a background of woven hair of the deceased. Ornate gold wire work could be used for the monogram or crest of the deceased. This can best be seen with the Stuart crystal ribbon slides, which are larger than rings.

A serpent with its tail in its mouth symbolized eternity, and was popular both for memorial jewelry and as a wedding band, and remains popular for this purpose today.

The fashion for memorial jewelry reached a positive frenzy with the death of Queen Victoria’s beloved husband Prince Albert, in December of 1861. By this time, styles had changed, and popular motifs were urns, or painted scenes of weeping willows in sepia tones. Often, there was a compartment on the back for a lock of the deceased hair. I once had one with what looked like a tiny piece of pinkish fabric. I was later told that this would have been a cornea from the deceased.

Today, we see a lot of jewelry with skulls and skeletons. This is now “edgy” fashion, and not meant to convey the earlier messages of remembrance, either of mortality or of the deceased.

By Andi Harriman and Audrey Friedman

The above article is copyright-protected, and cannot be reproduced whole or in part without written permission from Primavera Gallery.

To visit our website and see more, click here.